Menu-writing for multi-course dinner sucks. There…I said it. Until recently, I never really enjoyed it and when I asked professionals how they compose/curate/conjure one up, I was met with two parts mysticism (“I just write what the Universe says through me…it’s all about connecting with the Divine”), a heaping of cryptic shade-throwing (“Well, you have to first study and really understand the seasonality of the local terroir after which you compose layers of sometimes contradictory but simultaneously harmonious flavors”), and a pinch of astringency (“Actually…I don’t know. I make what I want OK?”).

“Artful” menu-writing seemed so mysterious, shrouded in veils of secrecy to prevent us uninitiated commoners from discovering just how the Stewards of Sauce-ry know to follow a biting Mizuna-Shiso salad with lightly roasted cod under a citrus foam. Without much insight into their cabalistic procedures, I often resorted to cobbling together pieces of different menus/recipes into some Frankenstein-esque monstrosity where beef curry was somehow followed by roast chicken on biscuits & gravy with bok choy (true story!). For a data geek like me whose Accounting degree had no business being in the kitchen, it was infuriating!

With a month away from my third pop-up dinner, a collaboration with the Filipino Kitchen and Pilipino-American Unity for Progress, and the bad taste of gravy-soaked bok choy in my mouth, I attempted to apply some unartistic nerdery to come up with a menu centered around our chosen theme of Philippine Independence Day. Unorthodox? Perhaps. Time-consuming? Oh yes indeed! But did it work? Read on…

Step 1: List and lay out

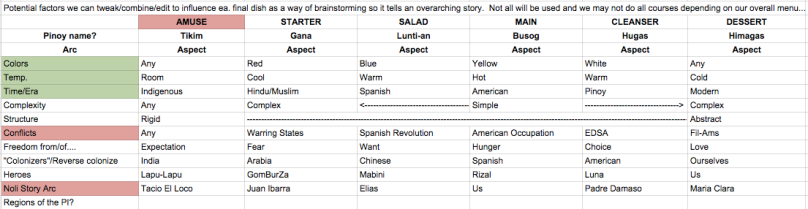

Stealing from Design Thinking principles I had picked up from college, I first listed aspects that make up a dish. Think of these as levers you could manipulate to influence the final dish: temperature, complexity, structure, style, and so on. You can also use broader, more abstract concepts, so long as they can follow a natural progression. Following the Filipino theme, I used ideas such as: Era (Indigenous, Muslim Trade, Spanish Conquest, etc.), People (characters from Jose Rizal’s Noli Me Tangere), Freedom (i.e. freedom from want, freedom of choice, etc.). The idea here being that dishes are ultimately a combination of the above aspects and this is a tool to draw inspiration from forcibly defined variables rather than some touchy-feely process. The same idea was somewhat applied to our cocktail pairings with components such as Spirit (Rum, Gin, Tequila), Strength (Tipsy, Drunk, Recovery), and degree of Sweetness.

Step 2: Combine and create

Probably the most fun part: thinking up the actual dishes! To come up with the individual parts of the menu, I randomly combined different aspects and imagined what a dish would look like. For example, I had to come up with a dish that was Hot (Temp.), Spanish (Era), and Rigid (Structure). The result was a Filipino take on several traditional Spanish tapas: Banderillas, Cojonudos, and Papas Bravas. The Banderillas followed a specific flavor order beginning with sour Monkfish kinilaw, salty dehydrated grapes, sweet Quail tea eggs, and back to a sour pickled radish. The Filipino Cojonudo replaced the baguette with a toasted pan de sal and Longganisa stood in for the usual Chorizo. The Papas Bravas, already near perfect in my opinion, used a colorful mix of blue Adirondack potatoes and ube (purple yam) topped with a bright yellow garlic-tahini aïoli.

On the other end of the spectrum was a dish that was to be Cool (Temp.), Pre-Colonial (Era), Abstract (Structure), and Yellow (Color). The inspiration was to create a dish that somehow represented an old story my dad told me of how some of the earliest settlers of the Philippines exchanged a Salakot (golden hat) and a Mangyad (pearl necklace) for some land with the indigenous tribes. I ended up with a light dish of turmeric-dusted mushrooms (golden hats) and peas (pearls) served on top of boat-shaped corn husks that was served towards the end of the meal.

The combinations here are endless and you’re only limited by your imagination around how to interpret the various aspects.

Step 3: Story and style

The final step is probably the easiest: fleshing out the “story” behind each dish and considering all the other factors around the dining experience such as plating and the individual ingredients. For the former, we chose to use disposable bamboo plates, cut banana leaves, and corn husks not only to cut down on the post-dinner dishwashing but also to reinforce the overall “feel”. Ingredients came about logically (coconut milk in the Red Curry we topped our Adobong Pantat with or using Zaatar in our Chinese-Arabic Salad) or thru an inspiration from what the market happened to be carrying (edible flowers at Union Square are back!). The themes we came up with in Step 1 were helpful here in ensuring we had a cohesive story that flowed from one dish to the next without being overly engineered or disjointed.

Our menu was designed to tell a story and I’ll point out that one can certainly question its “authenticity” or “historical accuracy”. However, I’d argue that writing a menu for these two goals will ultimately be flawed. We could certainly research every surviving text out there for what ingredients, equipment, and cooking method were used and try to replicate that, but we’ll never truly get to an exact replica of what existed in history…only a shadow of it. We’ll never be able to replicate the emotions felt by the diners of yesterday. Nor will we attach the same meaning to certain dishes that our ancestors did. Thus menu writing is as much a practice in re-writing/imagining our narrative as it is a process rooted in storytelling, an act powerful enough to touch people at their very core.

One of the moments that best illustrated the power of using a structured process to tell stories through food was when a diner had commented that our food “decolonized” his palate. That’s such a powerful statement to make considering just how engrained colonial influences are in our food. Ultimately, food has the power to shape the stories we tell and subsequently, ourselves. If your menus consist of meat-heavy entrees chockfull of sugar and “loud” ingredients, what does that say about you? If your menu prioritizes Instagram-ready looks over taste and has the air of judgment (I’m looking at you overbearing fruitarians), how does that affect the way you see the world?

As we cleaned the final few dishes and diners slowly trickled out, my thoughts rested on our dessert: Halo-Halo. The irony of Halo-Halo (translated as “Mix-mix”) is that a majority of it has become so standardized and predictable: the same fruit jellies from the same brands, doused with the same evaporated milk, topped with the same starchy beans, and overflowing with the same shitty ice as the next one. Ours had nothing in common in appearance but definitely in spirit: semi-frozen watermelon, fresh apricots, home-cooked sweet red beans, puffed heirloom rice, violas, and Spiced Milk similar in flavor to a Masala Chai; a seemingly illogical mixture. I looked around and the same could be said of our crew: 3 cooks, none of who grew up in the Philippines or ate “proper” Filipino food, food bloggers who had no formal culinary training, and community organizers whose focus was on the Filipino identity rather than food service. Yet it is this somewhat nonsensical approach that allowed us to reshape our collective stories and transfer some of that imagination to our diners.

Menu writing still sucks…I still can’t pull well-balanced menus out of thin air. But seeing it as a way of story-telling has made all the difference and that, in my opinion, is where the magic begins.

Special thanks to the Court Tree Collective for the space, sous chefs Christina Dominguez & Hillary Reeves, and of course…all the diners who broke bread with us.

Reading this gave me life (and is making me late for work…worth it)!

You make our stories come to life through food and I find it really inspiring 🙂

LikeLike

Hahaha! Glad I could get some good vibes in before the daily grind. Thanks for stopping by!

LikeLike

Cannot believe I’m only seeing this now! Love hearing about your process. This was really so much fun.

LikeLike

Can’t believe I’m only getting to reading this now! How did I not see sooner? Anyway, thrilled to be a part of it and I loved reading about your process. This was so much fun!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

And thank you for comin in clutch w/ the kitchen skills! Let’s do it again!?!? Or can we just hang out?……

LikeLike

Yes and yes!! I would *love* to do another one. Call me.

LikeLike

Yes and yes!! I would *love* to do it again. Maybe sometime in October? Anyway, call me!

LikeLike

Pingback: Hidden Apron at Home Ep. 4 Recap: On Cooking Creatively | The Errant Diner